There’s a special brand of charm that comes with cruising down highways during road trips, where the presence of company – or the lack thereof – elicits different experiences. When accompanied by like-minded travelling companions, the activity can be a wild, exciting affair centred on having a great time; alone, it can transform into a personal space for quiet solitude and contemplation.

At the core of it all, however, is this emphasis on the spirit of the journey, which foregrounds Japanese writer-director Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s Drive My Car. Adapted from a short story of the same name by renowned writer Haruki Murakami, the Cannes Film Festival contender takes viewers on an emotionally-wrenching three-hour ride along the lonely coasts of grief, regret, love, and healing.

The supersized runtime may, on the surface, seem like a questionable overextension of its original counterpart, but Hamaguchi proves otherwise with his storytelling prowess. Keeping faithful to the scant source material, the film expands on the narrative world of Drive My Car, bringing additional locations, new secondary characters, and a richer backstory to the silver screen.

What lies at the end of the road is a delicate, sincere, and poignant work that’s full of heart, even as it sputters at certain moments. Driving the story forward is one Kafuku Yusuke (Hidetoshi Nishijima), an accomplished theatre actor-turned-director best known for his multilingual Chekhov and Beckett productions. Marital bliss is a huge part of his life, established through 20 years of marriage with his screenwriter wife Oto (Reika Kirishima).

The mutual affection sees them often stimulating each other both intellectually and sexually, a routine that reinforces their perfect relationship – or so it seems. True to Murakami’s signature craft of using sex to convey the human touch (most notably in Norwegian Wood), these sensual moments offer an emotionally-charged space for desire, passion, and pleasure to mingle in a way that reminds of true, unwavering love. It’s during such times that Oto is gripped with artistic inspiration, as she strings together screenplay narratives while mid-coitus with Kafuku.

But the intimate displays are later revealed to be a facade for a marriage rooted in personal catastrophes, including the loss of an only daughter, and some health issues – one of which is Kafuku’s recently-diagnosed glaucoma. This descent into literal blindness later takes on a metaphorical form when he accidentally catches Oto in a sexual tryst with Takatsuki Koshi (Masaki Okada), a young and good-looking acting talent. Before he can clear the air with Oto, however, disaster strikes.

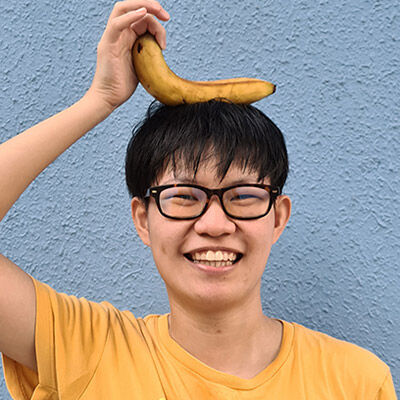

As Kafuku struggles with the emotional turbulence, a constant companion stands by his side: his beloved, red Saab 900. Here, the isolated comfort of a private space is accentuated by the way of cinematographer Hidetoshi Shinomiya, who masterfully juxtaposes tightly-framed interior shots against the vast, dull expanse of the city landscapes. Specifically for Kafuku, the vehicle also doubles up as a creative space where he recites his lines, with a cassette recording of the play as his prompting partner.

Though not by choice, this cherished space is later violated by a young hired chauffeur, Misaki Watari (Toko Miura) following a two-year timeskip. Having accepted an invitation to direct a polyglot production of Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya, Kafuku is now working at an arts festival in Hiroshima, but insurance rules prohibit him from driving. Instead, the task is relegated to Misaki, whose guarded and taciturn personality only allows for stilted, terse exchanges in the car. Eventually, long drives around the city pave the way for a blossoming friendship between the pair, as they expose still-healing wounds through painful confessionals and trusting displays of emotional vulnerability.

Their unlikely camaraderie is set against a backdrop of melodrama involving Kafuku’s complicated friendship with Takatsuki, in which they bond over their shared love for Oto, and the constant reminder of Sonya’s monologue from Uncle Vanya: “We shall bear patiently the burdens that fate imposes on us.”

It’s through the exploration of Chekhov’s play that Hamaguchi impresses with his creative genius. Murakami’s short story does indeed make a brief reference to it, but the man offers an added touch of finesse by framing it as the overarching motif, where the need to move on and continue to live in the face of disappointment, as conveyed in the above quote, mirrors the characters’ plight in Drive My Car. In line with the theatrical structure, both Kafuku and Misaki take several acts to free themselves from their emotional baggage and past trauma.

More notably, Hamaguchi has changed the premise of Kafuku’s apprehension for a more emotionally-nuanced touch. In the original narrative, he’s reluctant to surrender his car due to the sexist misconception that women lack the mechanical finesse; on the big screen, his unwillingness is attributed to an invasion of his fondest memories and personal space.

Another instance of Hamaguchi’s depth of creative freedom is the use of Korean Sign Language in Kafuku’s iteration of Uncle Vanya. While the multilingual elements highlight the role of the arts in bridging communication gaps, the latter emphasises the importance of paying attention to non-verbal cues via the silence-is-golden rhetoric.

Here, quiet and solitude don their best forms during lingering scenes that see detailed and rich visuals balancing out the scarcity of dialogue, and demonstrating the human connection, such as when a drawn-out shot captures Kafuku and Misaki raising their cigarettes toward the sky from the Saab’s open roof. Despite the extended room for contemplation and self-reflection, these moments take up the right amount of screen time without losing the interest of the viewer – an impressive feat in itself.

The emotional breadth of Drive My Car, meanwhile, is conveyed by Nishijima and Miura’s portrayal of their characters through haunted gazes and precise body language to express the anguish, grief, and emotional intensity that Kafuku and Misaki keep close to their chests. Both stars have shown mastery in the craft of show-not-tell performance, but the minute variations in facial cues come across as particularly convincing.

The feature, for all its visual and emotional scope, does falter slightly at certain points. There are times where conversations are more akin to directionless rambling, and the dramatic flair can get a little over-the-top. The scant deployment of Eiko Ishibashi’s music is also unfortunate, as its jazzy, mellow notes could have softened the mood in the more domestic, sentimental scenes.

At the heart of it, Drive My Car is a thoughtful and delicate introspection of what makes us human. It challenges the conventional model of romantic love and explores the process, all while finding solace in desolation – a commonality that ultimately binds the lives of different individuals. The longer-than-usual runtime may not be everyone’s cup of tea, but those who have their seatbelts strapped on will find that the journey is well-worth the emotional investment.

GEEK REVIEW SCORE

Summary

Drive My Car is an admirable undertaking of grief, love, and acceptance that offers a poignant experience, topped off with a rewarding emotional payoff at the end of the road.

Overall

9/10

-

Story - 8.5/10

8.5/10

-

Direction - 9/10

9/10

-

Characterisation - 9.5/10

9.5/10

-

Geek Satisfaction - 9/10

9/10