It’s all too easy to forget that films from renowned Japanese animation company Studio Ghibli are an exploration of real-world issues and thematically-related elements, especially when charming animation and bustling sights dance across the screen. Every story, regardless of its more whimsical or mature tone, has a message or two to convey, steering audiences on a journey to discover these lessons and experience the whole process themselves.

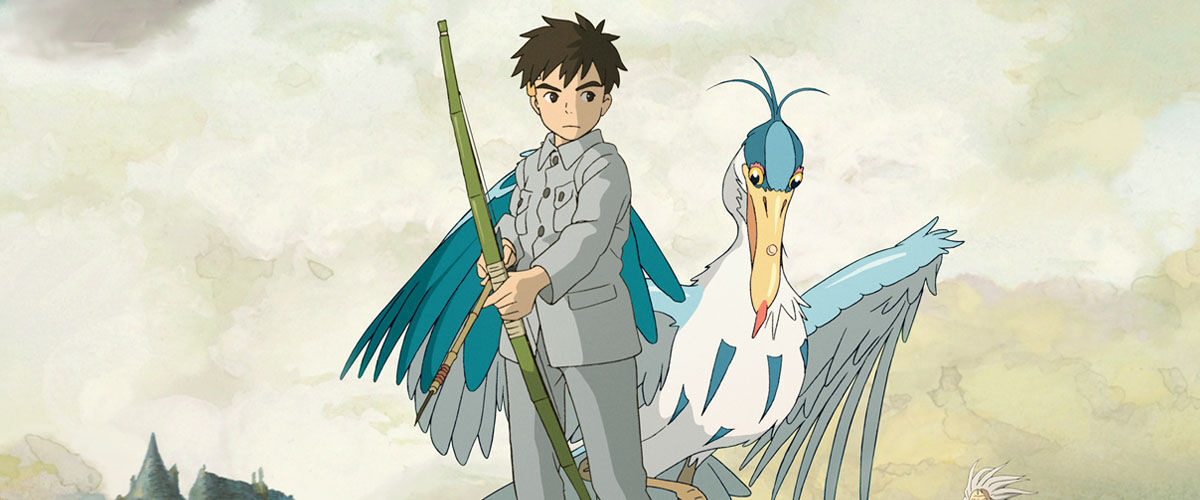

With The Boy and the Heron, Hayao Miyazaki’s first feature since 2013’s The Wind Rises, the connection to reality is made immediately apparent. The auteur’s supposed swansong dives right into a harrowing, cold-open bombing of a Tokyo hospital, where protagonist Mahito Maki’s (voiced by newcomer Soma Santoki) mother is trapped in the fire and dies, three years into World War II. The next year, the grief-crippled teenager and his father, Shoichi (Takuya Kimura), move into a sprawling estate by the countryside to live with his aunt, Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura), who’s newly-married to Shoichi.

Mahito struggles to settle in, maintaining a cold and detached exterior. If the 12-year-old isn’t getting bullied at school, he’s stewing in his grief, trying to deal with it by keeping himself busy, or confronting a pesky talking heron (Masaki Suda) that announces his presence via knocks on the window. After discovering a decrepit tower, protruding from the earth, on the estate, Mahito is quickly sucked into a series of events involving Natsuko’s mysterious disappearance, his desire to search for his late mother – declared not dead by the heron – and fantastical alternate worlds.

The storytelling craft is characteristic of the Miyazaki guarantee. Where the opening sequences are more reminiscent of Grave of the Fireflies (1988), directed by the industry veteran’s late colleague and mentor Isao Takahata, echoes of his earlier works like Princess Mononoke (1997), Howl’s Moving Castle (2005), and My Neighbour Totoro (1988) leave their mark in thematic exploration. The lines between magical and grotesque, accessible and peculiar, and childlike awe and complexity continue to be blurred.

But The Boy and the Heron also bears personal significance for Miyazaki, accentuating the heartfelt sincerity and human touch that Studio Ghibli films are always known for. Like Mahito, the auteur’s family fled Tokyo for the countryside when he was a young kid. His father worked in a fighter plane factory, and as highlighted in interviews, war has always plagued memories of Miyazaki’s younger self. He’s angry, too, at humans and the world at large, and channels that frustration through Mahito.

It’s as uneasy as it’s familiar, with the film spinning off several mainstay elements. There’s loneliness, childhood fear, and trauma, as well as escapism – exacerbated by the anxiety experienced in a world run by adults. Metaphorical representations are aplenty, from fire imagery to bodies of water alluding to drowning under the weight of grief. The references to war, in particular, are inherited from The Wind Rises (originally intended to be Miyazaki’s last outing), interweaved into a tale that re-examines what it means to be human through times of crisis. Oh, and who can forget about the hero’s journey structure?

Notably, the nod to Genzaburo Yoshino’s 1937 novel “How Do You Live?” – which is, in fact, the Japanese title – introduces more nuance to the exploration of loss. The literary classic appears in the film, serving as Mahito’s guide as he navigates the entanglement of life and death during a pivotal part of the story. How does one find the strength to carry on when grief pulls you down? How can you fight against the whirlpool of helplessness, anger, and suffering? These existential questions drive the narrative forward, and through implication rather than explanation, demand an answer from viewers.

Despite the emotionally raw overtones, The Boy and the Heron isn’t all doom and gloom. Longtime collaborator Joe Hisashi hits all the right notes for a soul-stirring, somber stage, but the composer is hardly a stranger to crafting bright, playful tunes, which play nicely into lighthearted moments. Like the susuwatari, or Soot Sprites, of My Neighbour Totoro and Spirited Away fame, white ghost-like creatures called the warawara easily draw out a smile – sometimes an excited coo or two – with their adorable and spirited (hah) demeanour.

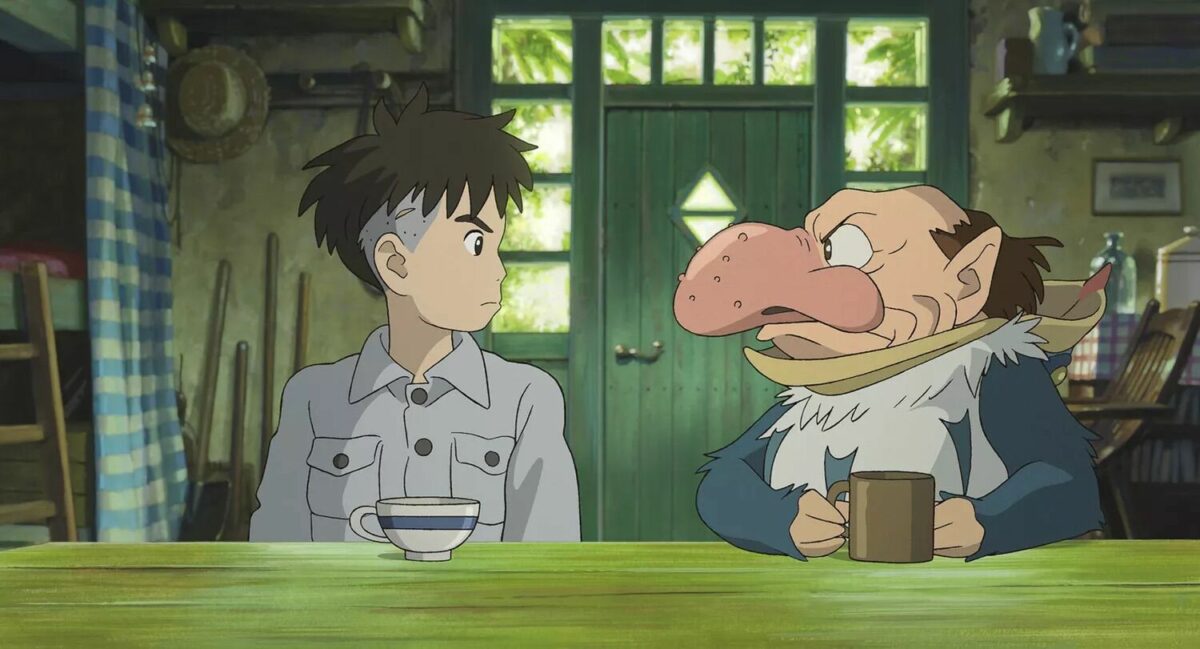

The eclectic cast of characters adds more charm and personality to the film, presenting an interesting dynamic between Mahito and the companions he meets along the way. The heron may be rough around the edges, but has his fair share of respectable qualities. His relationship with Mahito is fleshed out well, unfolding in a genuine manner that evolves from rocky beginnings into begrudging camaraderie.

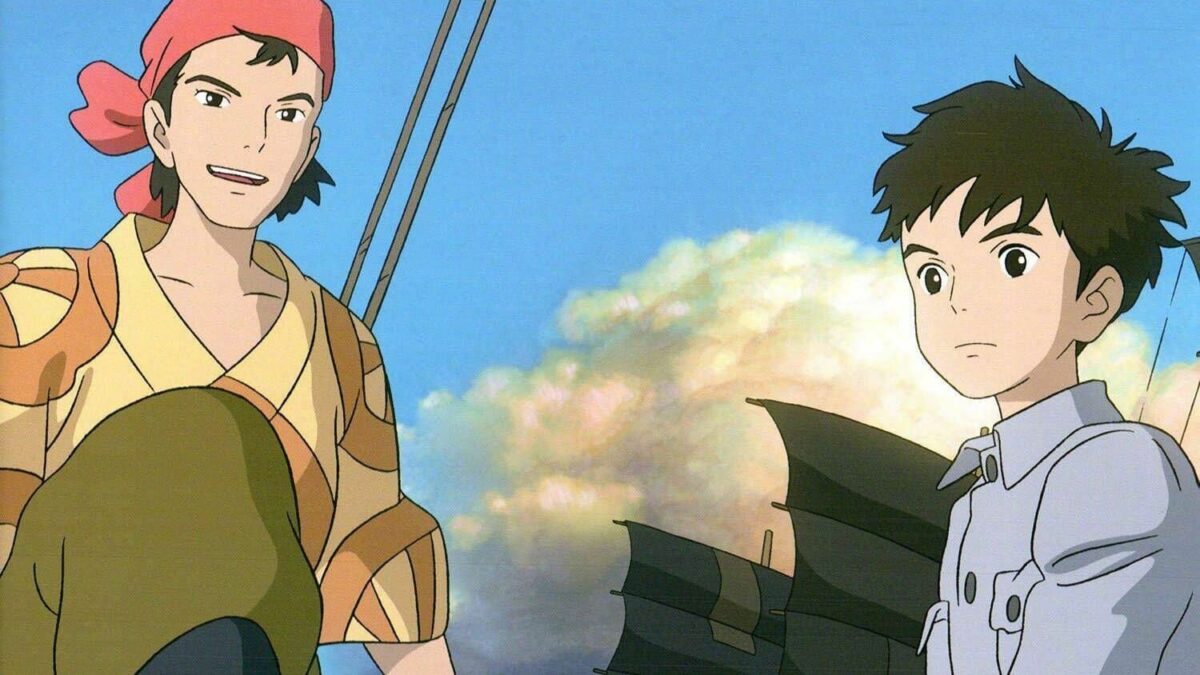

However, there’s no denying that the spotlight belongs to the female characters here. In having a rare male lead, The Boy and the Heron marks a departure from Miyazaki’s usual women-led narratives, such as Princess Mononoke, My Neighbour Totoro, and Ponyo (2008). This same display of empowerment and individuality has carried over, taking the form of the stern yet compassionate mentor-like figure Kiriko, the kind-hearted protector Himi, and the mischievous, lively old house servants.

Attention to detail is par for the course when it comes to Studio Ghibli, and The Boy and the Heron certainly delivers on the promise. While the animation powerhouse’s movies have always been visual masterpieces, Miyazaki’s latest adventure is a breathtaking spectacle that straddles the fine line between beautifully-drawn food, gorgeous, highly-detailed scenic shots, and lull moments. More than just a platform for contemplation, these long stretches of time are also an effective representation of navigating grief and loss in the real world, where detachment and at times, dissociation follows a lacking sense of time or space.

Perhaps the only drawback is the lack of fresh elements. The animated feature is a familiar sight for Miyazaki devotees and Studio Ghibli fans alike, much like a warm homecoming after being away for a few years. In fact, some may argue it’s a little too comfortable, but that’s arguably the point – The Boy and the Heron leans more towards an exercise in reflection and mediation than storytelling. It’s nothing particularly groundbreaking, considerably run-of-the-mill, even, by the filmmaker’s standards, and doesn’t pack a lot of surprises. Yet, it continues to draw viewers in, touch their hearts, and leave them with a poignant, thoughtful introspective.

As the supposedly final ode to his career, the movie serves to encapsulate Miyazaki’s decades-long journey of crafting and telling profound, entertaining narratives. Following critical reception and outstanding box office performance in Japan, Miyazaki has confirmed that it’ll no longer be his last work.

Still, the question remains: How do you live? For the 82-year old, it’s always been about dreaming and conveying them to others, culminating into a storied legacy for the ages.

GEEK REVIEW SCORE

Summary

The Boy and the Heron marks a triumphant return for Hayao Miyazaki, who weaves together an intricate, moving tale about life, death, and everything in between, and tops it off with his characteristic thematic and artistic touch.

Overall

8.9/10-

Story - 8.5/10

8.5/10

-

Direction - 9/10

9/10

-

Characterisation - 9/10

9/10

-

Geek Satisfaction - 9/10

9/10